Up close with the Red Planet

Mars, our neighbouring planet, is considerably smaller than the giants Jupiter and Saturn, but still it really fascinates us.

Bernd Gährken

Bernd GährkenOne of the reasons for this is that we have already sent some research satellites and exploratory probes there, which have been able to send us extensive photographic material, with which we have able to build up a rather impressive picture of the surface.

There are craters, rilles, valleys (Valles), lowlands (Planitia), mountain ranges and the highest mountain in our solar system - the 26 kilometre tall Olympus Mons volcano.

The ever-present idea of potential life also contributes to our fascination with the Red Planet. Was there ever liquid water on the surface? Could we find the simplest bacteria there, or even lichen that might give us an indication of organic life? We are still in the process of clarifying these and other questions about the geology and origins of Mars.

So until the day that perhaps even humans can land on Mars, we must be content with the data and photos from these probes, together with our own observations.

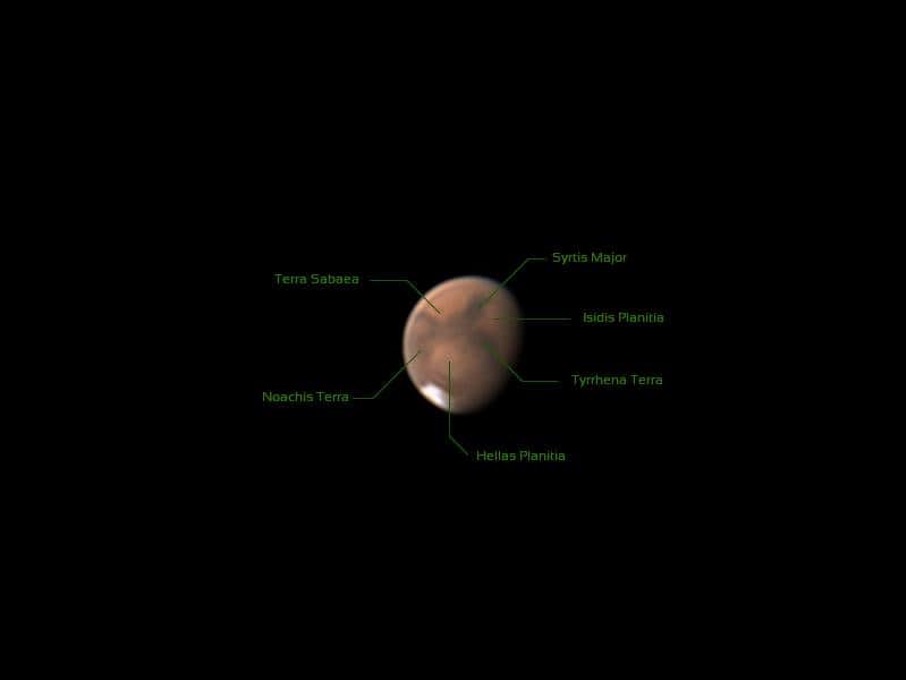

Mars image taken with an 8" SC, ZWO ASI 224MC, ADC - with very good seeing in August 2020 (Photo by J. Bates, Berlin)

Mars image taken with an 8" SC, ZWO ASI 224MC, ADC - with very good seeing in August 2020 (Photo by J. Bates, Berlin)Why is its opposition useful for observation?

During an opposition, the Earth is exactly centred on a line between the Sun and Mars (the same position applies, for example, when we see the full Moon). This happens every two years.

This means that the planet, in this case Mars, is at its lowest distance to Earth at around the time of its opposition and is also, from our point of view, completely illuminated by the Sun. By the way, this only works with those planets that are located outside of the Earth's orbit. Mercury and Venus are never in opposition. The Earth can never be between them and the Sun.

A photo of the Red Planet by Bernd Gährken

A photo of the Red Planet by Bernd GährkenThere's a lot to see when observing Mars. Starting with a telescope with an aperture of around 100 mm upwards, you can see dark plains, white polar caps or even brighter cloud structures. Of course, a larger telescope aperture will be able to resolve comparably more detail.

Schmidt-Cassegrain or Maksutov telescopes are especially popular devices for planetary observation. They offer a long focal length, ensuring a sharp and high-contrast image. In addition, they are also significantly more compact and lightweight than a corresponding refractor. Even using large binoculars you will usually see no more than an orange dot or at best a small disc, whereas with a 200-mm Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope, for example, you can make a detailed observation of Mars similar to that seen in the picture above. A special planetary camera will bring out even more structures on Mars. Models from the Omegon veLOX series or the ZWO ASI are particularly suitable for this purpose.

Using an ADC (atmospheric dispersion corrector) will improve the atmospheric turbulence for both visual use and for photography. It compensates for the effect of atmospheric dispersion and helps to reduce colour fringes on bright objects such as planets. Planetary photographs will be even sharper with an ADC.

Author: Jan Ströher

Jan is a linguist and product manager for our astronomy products.

Jan studied English, Romance languages and business administration and then worked as an account manager in the aviation industry. Since he was young, he has been interested in natural sciences, especially astronomy: at the age of 15, he made his first observations with a Newtonian telescope from his parents' balcony.

Jan loves the great outdoors, and besides astronomy, he is also interested in animals and meteorology. His favourite objects in the sky are the big planets, Wolf-Rayet nebulae and globular clusters.

Languages: German, English, Spanish