The Lord of the Rings

Even a 80mm telescope will conjure up the Lord of the Rings in the eyepiece for you. No sight inspires beginners as much as Saturn can.

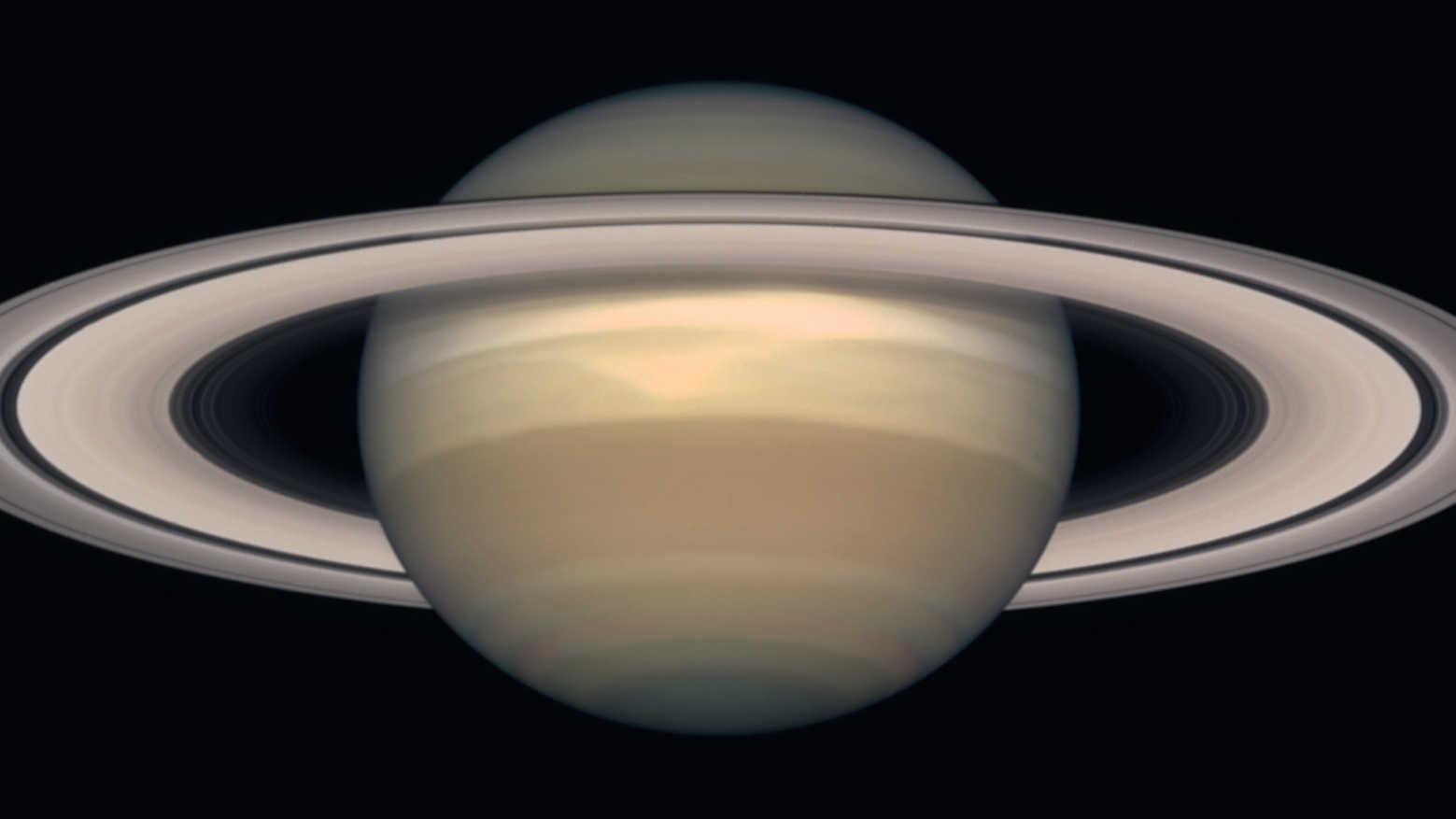

The unique ring system crowns your first sight of Saturn. NASA and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

The unique ring system crowns your first sight of Saturn. NASA and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)Observing the rings of Saturn

No other planet in our solar system is as fascinating as Saturn. It elicits an excited “wow” from many beginners, because there’s one special feature that crowns the sight of the gas giant: its unique ring system, which is more pronounced than with any other planet. And you can successfully observe this natural spectacle even with a smaller telescope.

Saturn, which counts as one of the gas giants, is the second largest planet in our solar system with a diameter of 120,536km. At an average distance of 1.4 billion kilometres, Saturn takes about 29.5 years to orbit the Sun. It rotates very quickly around its axis, taking just 10h 28min. As of today, we know of a total of 62 moons that orbit the gas giant. However, its special feature is its ring system, although this is not uncommon in principle. Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune also have rings, but they appear too faint to be seen with amateur telescopes.

Multiple rings

In total, Saturn is surrounded by a system of more than 100,000 individual, completely separate rings. The innermost ring is 7,000km above Saturn’s atmosphere and has a diameter of 134,000km. The huge outermost ring has a diameter of 960,000km. The apparently solid structures actually consist of billions of individual rocks and blocks of ice, ranging in size from a grain of dust up to the size of a house. The ring system is not thick, being less than 1km deep. However, there are also sections where the stack of rock and ice material can be several kilometres high. The Cassini Division is a large gap in the ring system, around 4,700km wide. Recent research results show an even more vast structure: an invisible ring of fine dust particles that surrounds Saturn at a distance of up to around 25 million kilometres.

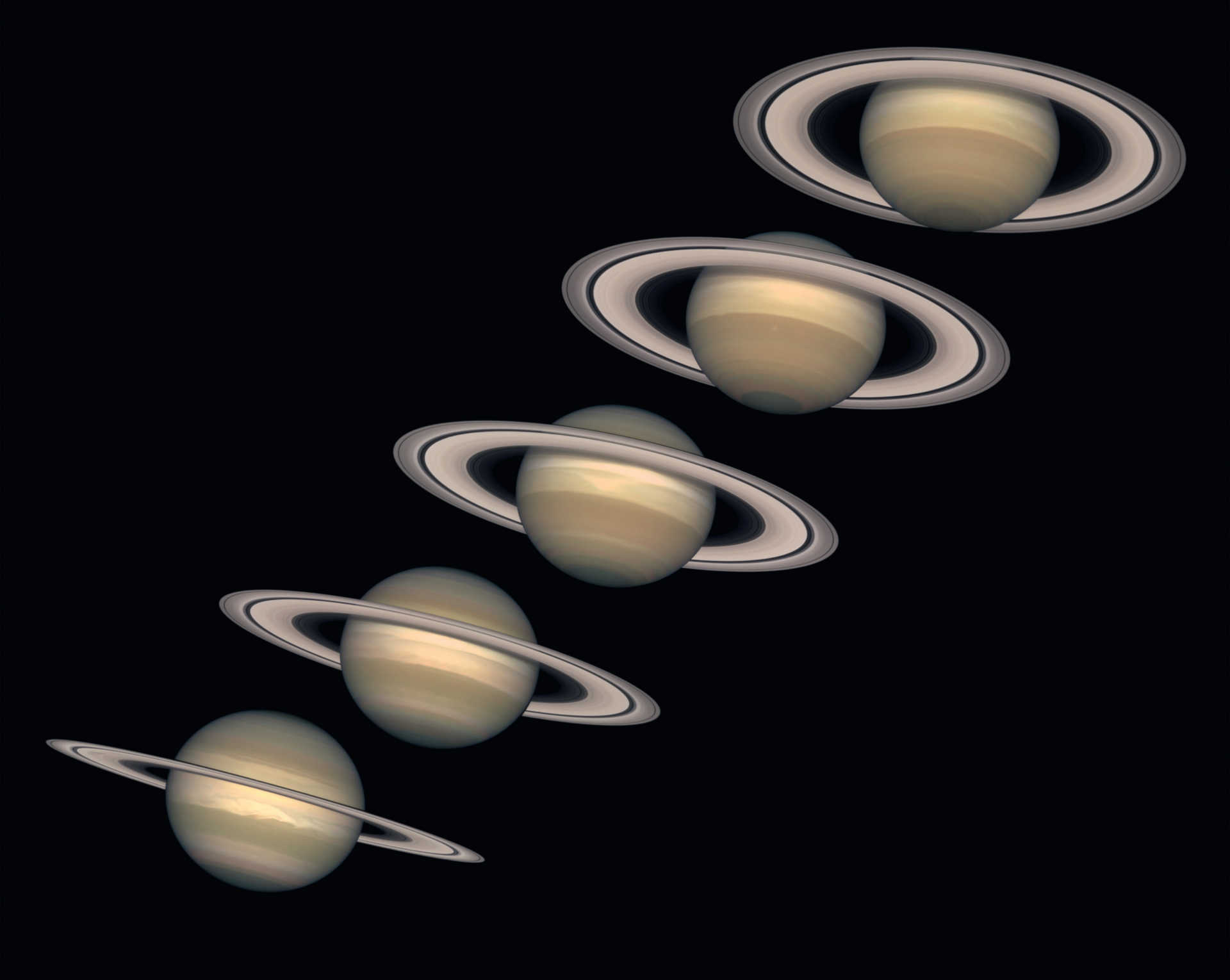

Saturn, as viewed from Earth in the years 1996 to 2000. NASA and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

Saturn, as viewed from Earth in the years 1996 to 2000. NASA and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)A short ABC of the rings

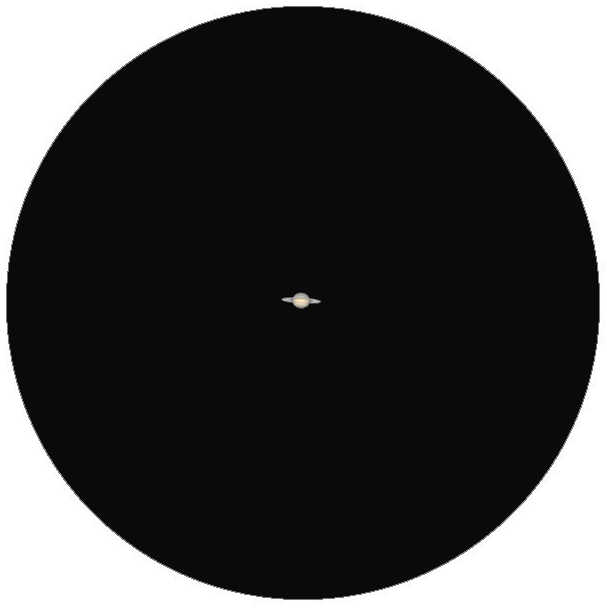

Illustration: Saturn is actually only relatively small when observed with a telescope, here an example using telescope with a 60mm aperture and 60x magnification. L. Spix

Illustration: Saturn is actually only relatively small when observed with a telescope, here an example using telescope with a 60mm aperture and 60x magnification. L. SpixSaturn's ring system consists of seven main rings. Starting from the inside, these are known as the D, C, B, A, F, G and E rings. However, with a telescope, only the A, B and C rings, which have a maximum diameter of 270,000km, can be seen. Even through a small telescope with a 60mm aperture you can see two of these rings: the dark outer A ring and the bright inner B ring. With an 80mm aperture, it is possible to identify the Cassini Division as a dark, fine line, as if drawn with a compass, which separates the two rings from one another. On a night when the air is calm, the scene looks completely three-dimensional and almost unreal. The faintly shimmering inner C ring, on the other hand, can only be seen with a telescope with a larger aperture.

Sometimes above, sometimes below

Due to the inclination of Saturn’s axis of almost 27° compared to the ecliptic, the angle at which we see the rings changes continually over the course of a 29.5-year Saturn year: sometimes you are looking at the ring system from above, sometimes directly from the side, so that the rings are practically invisible, and sometimes from below. In 2017 the rings appear at their maximum open angle once more, so that we can look at the north side of the rings.

Practical tip

You can clearly see the A ring and the B ring using a telescope with a 80mm aperture. The two are separated by the dark Cassini Division. Mario Weigand

You can clearly see the A ring and the B ring using a telescope with a 80mm aperture. The two are separated by the dark Cassini Division. Mario WeigandThe rings of Saturn through a telescope

It’s straightforward to observe the features of the rings of Saturn using a small telescope with an 80mm aperture. They can be clearly seen at a magnification of 60×. With a higher magnification of around 100×, the sight becomes three-dimensional and the rings seems to float around the planet. The Cassini Division is more difficult to identify: this requires very calm air, which will allow you to use a magnification of around 100× and more. The best way to find the Cassini Division is to concentrate first on the outer areas of the ring, left and right of the planet. There, due to the distortion caused by the perspective, the Cassini Division appears wider and so easier to identify.

Author: Lambert Spix / Licence: Oculum Verlag GmbH